By Rebecca K. Smith, CLDC Board Secretary & Cooperating Attorney

By Rebecca K. Smith, CLDC Board Secretary & Cooperating Attorney

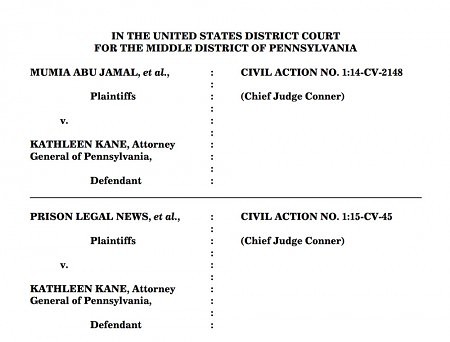

Last week, a federal court in Pennsylvania struck down a state law aimed at restricting the free speech rights of prisoners. In Mumia Abu Jamal v. Kane, the court addressed a new state law in Pennsylvania called the “Revictimization Relief Act,” which attempted to stop accused or convicted criminals from publicly expressing viewpoints that might offend the alleged victims of their crimes. The court found the law unconstitutional because it had an unlawful purpose, was vaguely executed, and was patently overbroad in its scope. The court held: “A past criminal offense does not extinguish the offender’s constitutional right to free expression. The First Amendment does not evanesce at the prison gate, and its enduring guarantee of freedom of speech subsumes the right to expressive conduct that some may find offensive.”

The “Revictimization Relief Act” stated that “a victim of a personal injury crime may bring a civil action against an offender . . . for conduct which perpetuates the continuing effect of the crime on the victim.” The law defined “conduct which perpetuates the continuing effect of the crime on the victim” as including “conduct which causes a temporary . . . state of mental anguish.” Additionally, the law allowed local district attorneys to file such lawsuits “on behalf of the victim.” 18 PA. CONS. STAT. 11.1304. Essentially then, the law allowed “victims,” or district attorneys, to file civil lawsuits against “offenders” who cause “a temporary [] state of mental anguish” to the “victims.”

The bill was introduced in 2014 in the Pennsylvania legislature three days after Goddard College in Vermont had announced that Mumia Abu Jamal would be its commencement speaker. Abu Jamal, an African-American writer and journalist, was convicted in 1982 for the murder of a police officer. The fairness of Abu Jamal’s trial and his guilt/innocence are hotly debated. Supporters of Abu Jamal cite to racial biases in the trial proceedings, the political climate in Philadelphia at that time, and their belief that a different individual was actually responsible for the officer’s death. In 2001, a federal court overturned Abu Jamal’s death sentence, but he remains in prison for life without a chance of parole. Abu Jamal has continued to work as a journalist and regular political commentator from behind bars.

The representative who introduced the “Revictimization Relief Act” bill in the Pennsylvania state legislature mentioned a “convicted killer” who was “traumatizing the victim’s family.” The bill passed in less than two weeks. When Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett signed the bill, he stated that the bill was “inspired by the excesses and hypocrisy of one particular killer.” The repeated references to Abu Jamal indicated that the bill was intended primarily to stop Abu Jamal from continuing to speak out, but the bill would also have the same impact on other prisoners attempting to exercise free speech.

In Mumia Abu Jamal v Kane, the federal court first held that the law had an unlawful purpose to restrict the free expression of a particular group of people based solely on whether the content of the expression might offend someone. The court stated: “the First Amendment demands tolerance of even hurtful speech so that we do not stifle public debate.”

The court also held that the law was too vague to meet the demands of the Constitution. The law was so vague that it could have been construed to apply to the accused (but not convicted), the convicted, the exonerated, and third parties who publish the speech of any of the foregoing individuals. The law was also too vague in its description of what kind of conduct was unlawful: merely causing “anguish” to a victim is simply too subjective to pass Constitutional muster.

Finally, the court found that the law was too broad to meet the demands of the Constitution. Essentially, the law could have been applied to any expressive activity by any person who had ever been convicted of a personal injury crime, so long as the purported victim asserts that he or she feels anguish. The court rejected the law as unconstitutionally overbroad, noting that if upheld the law could prohibit pardon applications, clemency petitions, public expressions of innocence, apologies, confessions, or legislative testimony regarding prison conditions or justice programs; in short, the law would have prohibited any public speech or written work. The court even noted that the law could prohibit a pretrial detainee’s right to profess his or her own innocence prior to trial.

In sum, the court held: “The First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech extends to convicted felons whose expressive conduct is ipso facto controversial or offensive. The right to free expression is the shared right to empower and uplift, and to criticize and condemn; to call to action, and to beg restraint; to debate with rancor, and to accede with reticence; to advocate offensively, and to lobby politely. Indeed, the ‘high purpose’ of the foremost amendment is perhaps best displayed through its protection of speech that some find reprehensible.” The court then issued a permanent injunction against implementation of the unconstitutional law.