CONTEMPT OF COURT: NOT JUST A FEELING

Part II of a Contempt Primer for Activists and Their Communities

by Sandra Freeman, CLDC Senior Staff Attorney

*This is not intended as legal advice, but is general information. If you are facing criminal or civil contempt, you should contact a lawyer for formal legal advice.

Case Study: Using contempt to silence labor and social justice activism

During 1989 and 1990, coal miners across Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky went on strike to demand that the Pittston coal company implement safety measures and restore healthcare benefits for the miners whose families and livelihood depended on enduring hazardous working conditions. United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) went on strike on April 5, 1989, and the company immediately brought in scab workers to maintain production levels. The striking workers used nonviolent direct action to slow down production and make their demands known: soft road blockades, sit-ins, and picketing in front of Pittston’s headquarters in Lebanon, Virginia. The strike grew to over 50,000 participants according to the AFL-CIO, with actions taking place across eleven states, and a full scale encampment near Carbo, Virginia called “Camp Solidarity,” that provided support to strikers and their communities.

Within a week of UMWA declaring a strike, the company filed a lawsuit in Virginia state court asking the court to forbid (“enjoin”) the union from picketing and other activities, which the court opined were illegal. When mass arrests did not deter the striking workers or their supporters, the Virginia court entered a series of escalating orders finding the union in civil contempt and imposing sanctions in the form of steadily increasing fines. By the time the case reached the United States Supreme Court, the fines totaled over $64 million, with $12 million payable to the coal company and over $50 million payable to various Virginia government agencies. The Supreme Court reversed the fines, stating that they were significant enough punishment to constitute “criminal” as opposed to “civil” contempt, and therefore could be imposed only after a jury trial. This was a huge victory not only for unions but for all people who face punitive (punishment instead of coercive) contempt charges and fines for asserting their rights in the face of corporate abuse.

Hazel Dickens singing in support of striking miners & families on the Pittston Coal picket line, which began on April 5th 1989. pic.twitter.com/zoXfBmavlk

— Appalshop (@Appalshop) April 5, 2018

Here at CLDC, we are vocal and vigorous about our defense and support of those facing state repression for their involvement in social and political movements for liberation. At times this has meant providing support to grand jury resisters and others who are held in contempt, and we do a lot of education specifically about contempt in the grand jury context. With social movement activity increasing over the course of the past two years in response to COVID-19, the murder of George Floyd, and the subsequent uprisings, many more people find themselves interacting with courts and decision-making bodies of all kinds that have the power to hold anyone who appears before them in contempt. The purpose of this blog series is to give activists and movement participants the information and tools they need to fight back against State repression, allowing them to continue the work to reach the goals of the movements they are a part of.

In this blog series, we will answer: What is contempt of court? Who can be held in contempt? What are your rights if you are threatened with contempt? Check out Part I HERE, and stay tuned for an in-depth Part III case study on Chevron’s use of contempt to persecute human rights attorney Steven Donziger.

“Civil” or “Criminal” Contempt?

What attorneys and judges refer to as “civil contempt of court” typically means a scenario where a party in a civil case is accused of deliberately defying a court’s order(s) in a way that causes monetary damages to, or somehow harms, the other party in the case. In these types of situations, the rules of court allow for the harmed party to move or ask the court to find the other party in contempt. (See, e.g., Fed. R. Civ. P. 11; Colo. R. Civ. P. 107; Va. Code § 8.01-274.1.) The penalties for civil contempt can be remedial — remedying the harm or making the harmed party “whole” — or punitive — punishing the party in contempt.

Contempt proceedings and sanctions — whether fines or imprisonment — are deemed to be “civil” as opposed to “criminal” if they are conditional — that is, they can be avoided by compliance with the court’s order. Contempt sanctions are deemed to be “criminal” if the punishments are unconditional—obeying the court order does not relieve you of the punishment. Criminal contempt penalties “may not be imposed on someone who has not been afforded the protections that the Constitution requires of such criminal proceedings.” (Hicks v. Feiock, 485 U.S. 624, 632-33 [1988]).

There are significant differences between the legal rules regarding remedial (civil) and punitive (criminal) measures designed to address contempt of court, including different burdens or levels of proof required to punish defiance of a court order; these differences are so significant and technical that courts themselves often have trouble distinguishing between remedial versus punitive measures. The Supreme Court has recognized that “contempts are neither wholly civil nor altogether criminal. And it may not always be easy to classify a particular act as belonging to either one of these two classes.” (Gompers v. Buck’s Stove and Range Co., 221 U.S. 418, 441-42 [1911]).

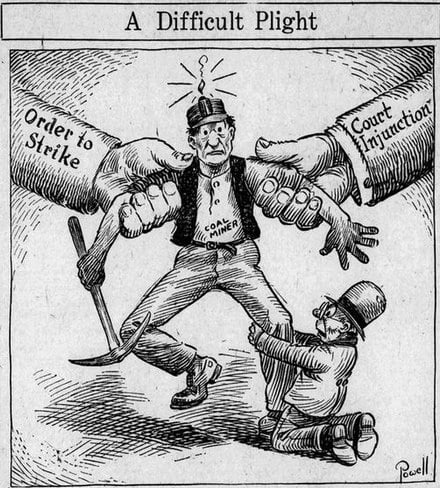

Political cartoon, Omaha Daily Bee (1919).

Gompers was a United States Supreme Court case about the use of injunctions/court orders to forbid protected First Amendment activity (in the Gompers case, speech advocating for a union boycott), and the court’s use of the contempt power to enforce those orders. Throughout the history of the United States, corporations have resorted to court injunction orders to repress strikes and union organizing power. (See, e.g., United States v. United Mine Workers of America, 330 U.S. 258 [1947], upholding millions of dollars in criminal and civil contempt sanctions against miners who violated court order prohibiting strike at government-owned coal mines; North American Coal Corp. v., Local Union 2262, 497 F.2d 459 [6thCir. 1974], reversing convictions of union officers held in contempt for wildcat strike.) This repressive use of court orders and weaponization of the court’s contempt power by corporations continues today, with the threat of contempt still hovering over workers exercising their right to strike and demand better conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Judge issues injunction against striking Kentucky distillery workers). The state of Colorado even has a law on the books specifically about the rights of striking workers accused of contempt for violating court injunctions and orders. (See C.R.S. 8-2-109.)

SLAPP Cases & Civil Contempt

Given the repressive history of the corporate use of contempt as a litigation strategy, it should come as no surprise that questions around contempt of court arise when corporations and other powerful actors engage in bullying SLAPP (“Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation”) litigation. As SLAPP suits have become more common, CLDC has seen extractive industries and other powerful plaintiffs file SLAPP suits and are not shy about asking the courts to use the contempt power to fine and jail activists as a means of chilling the SLAPP defendants’ lawful and constitutionally protected activities (as well as their community/allies).

Here at CLDC, we admire and support the efforts of Appalachians Against Pipelines and others on the east coast defending the Appalachian mountains and rivers from the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) and other extractive projects in Virginia and West Virginia. The courageous folks resisting the MVP have faced militarized police raids, criminal charges, SLAPP suits, contempt of court findings, and fines due to their principled defense of the forest, streams, and mountains (as well as rural life). Many were arrested and charged over the course of the powerful Yellow Finch tree-sit blockade that lasted nearly three years. Land defenders occupying trees in the route of the pipeline have been held in contempt after courts ordered the protestors to leave the trees. Landowners themselves on the MVP route have been found in contempt for allowing tree-sitters on their property in defiance of a court order permitting the Mountain Valley Pipeline to build and operate against the will of the landowners. Nonetheless, the pipeline remains incomplete due in part to the dogged, courageous acts of resistance in the communities of West Virginia and Virginia– but these acts have clearly come at a cost to the principled individuals and communities asserting their rights to respect the land and live in a world free of pipelines.

Hand painted banner hanging in the forest in resistance to the MVP (2019).

The small but significant differences between the types of contempt proceedings and a nuanced understanding of the legal rights of potential contemners are exactly why it is so important to consult with a trusted attorney as soon as possible when thinking about what to do or how to respond to a lawsuit, court order, or subpoena of any kind. You should consult with a trusted attorney as soon as you receive a subpoena or are placed under a court order of any kind, especially ones related to protected First Amendment speech and activity.

Contempt of Court threats and punishments are just another form of State repression leveled at activists engaged in successful campaigns that cause reputational and other harms to capitalist profiteers. The State and its henchmen cannot take what does not exist—consider document destruction protocols, consult with financial advisors and when engaged in mass movement political work, take yourself seriously because the government and corporations do.

Grand Jury Contempt

Grand juries (mentioned in the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution) are secret investigative bodies made up of ordinary citizens who investigate alleged criminal activity to determine whether to issue a federal felony charging document called an indictment.[1] The job of a grand jury is not to determine whether someone is guilty or innocent of a crime, but to act as a screen and make sure that the state is not charging anyone with a felony without demonstrating probable cause that a crime was committed. T Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure imposes a secrecy requirement on all grand jury proceedings and deliberations, meaning the court and records are secret and closed to the public, the accused, and even to defense attorneys for the witnesses.

The grand jury is a colonial construct originating in England. The original intent of including the grand jury in United States law was to provide a way for the members of the public to act as a check on the federal government’s charging power and authority, in order to protect ordinary people “against hasty, malicious and oppressive persecution,” and to make sure that criminal charges were not “dictated by an intimidating power or by malice and personal ill will.” (Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375, 390 [1962]) In practice, however, the grand jury is a secretive process controlled by the prosecutor that is destructive to movements and individuals because it is easily abused or used for improper political purposes. These abusive practices are nothing new. Shortly after the American Revolution, federal grand juries convened in the newly-minted republic often consisted of Federalists who made militantly partisan reports and advanced political prosecutions against Republicans. (See R. Younger, The People’s Panel: The Grand Jury in the United States, at 44-55 [1963]. See generally, Schwartz, Demythologizing the Historic Role of the Grand Jury, 10 Am. Cr. L. Rev. 701 [1972])

Nearly 250 years later, the federal government continues to use grand juries in a way that provokes fear and mistrust in dissident communities and movements. The secret nature of the grand jury contributes to the atmosphere of fear and repression created by issuing subpoenas that command individual witnesses within the community to testify; the witnesses are then required to either participate in a secretive process without basic constitutional protections or risk incarceration for refusing to participate.

Steve Martinez resisted a grand jury in both 2016 and 2021.

CLDC attorneys have represented and supported many witnesses in their principled refusal to cooperate with the secretive colonial grand jury investigation process which can drag on for years. In December 2016 Indigenous water protector and grand jury resistor Steve Martinez was called to testify to a federal grand jury about the hours following the brutal police attack on peaceful water protectors on the Backwater Bridge in Morton County, North Dakota on November 20, 2016. On that night, Martinez drove CLDC client Sophia Wilansky to the hospital after she was seriously injured by police munitions thrown directly at her. North Dakota police and the federal prosecutors behind the grand jury have continually sought to blame Sophia and #NoDAPL Water Protectors for her injury. Thanks to the work of Steve’s legal team the subpoena was withdrawn in the early months of 2017, but in late 2020 he was re-subpoenaed back to a federal grand jury in Bismarck when the federal government claimed to still be investigating the source of Sophia’s injury. In February 2021, the judge found Steve in contempt and ordered him to spend months in jail during the COVID-19 pandemic. After having spent most of February in custody, he was briefly released and subpoenaed to appear before the grand jury again in March. At the second appearance, he was taken back into custody and held for a cumulative total of more than 60 days. Steve was finally released in April of 2021 thanks to the intrepid work of his support crew and lawyers Moira Meltzer-Cohen and Ralph Hurvitz, but not before losing months of his life to a secretive and abusive process.

When movements discuss contempt of court in the grand jury context, it is usually in circumstances involving a witness who is refusing to comply with a subpoena to testify before a federal grand jury. The first line of defense for the person who has been served a subpoena is to reach out to their community for support and to seek an attorney who is experienced in grand jury resistance. Once trusted counsel is secured, they will work to investigate the basis of the subpoena and then ask the judge overseeing the grand jury to move to cancel or quash the subpoena for a number of reasons, including that the subpoena seeks privileged information, invades protected First Amendment rights, was issued in bad faith, or is based on unlawful electronic surveillance, among others. If a reviewing court denies the motion to quash the subpoena, the witness will be required to appear in front of the grand jury alone. If at that point the witness still refuses to answer questions, the court can order the witness to appear at a contempt hearing.

Because this type of contempt hearing is considered “civil” and not “criminal,” the court does not have to provide the witness with a jury, a trial, or a defense attorney before finding the witness in contempt of court and imposing sanctions. The “Recalcitrant Witness Statute” allows judges to order imprisonment of a non-cooperating grand jury witnesses, and says that this imprisonment can last until the witness cooperates or until the case ends or the grand jury adjourns. (See 28 U.S.C. § 1826) The secrecy of the grand jury, abbreviated timelines, and ability of judges to jail witnesses without a full public trial are just a few of the reasons why it is critically important for anyone who receives a grand jury subpoena to contact a trusted attorney who is experienced in grand jury litigation as soon as possible.

Grand jury resistance has a long and vibrant history. While the risks of non-cooperation are high, it remains the most effective way for participants in social and political movements to protect themselves against further repression. CLDC has a number of educational resources on grand juries. You can request access to CLDC grand jury related webinars here. We also recommend listening to the Crimethinc podcast episode “Surviving a Grand Jury,” which features three first-person accounts of resistance.

[1] Some state criminal punishment systems also rely on grand juries to issue indictments. This piece is meant to concentrate on the principles applying to defense of witness in contempt of a federal grand jury.