July 29, 2020 – A Springfield Black Lives Matter Retrospective

Anyone present during the Black Unity-led protest in Springfield’s Thurston Hills neighborhood on the night of July 29, 2020, will likely remember it forever. The protest was focused on supporting a local Black resident and educating a community about the racist history of nooses in Oregon. But the official response was gratuitous police violence in collusion with racist counter-protesters against Black people and their allies, exemplifying the precise reason people had been continuously protesting across the country since the May 25, 2020, police murder of George Floyd. In response to the blatant police abuses in our community, the Civil Liberties Defense Center (CLDC) represented numerous organizers in criminal courts and filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the Springfield Police Department (SPD), the City of Springfield, and its officers. CLDC is an abolitionist legal organization that recognizes the inherent racism of the U.S. legal system and that reform of police departments and the carceral state will not bring about the necessary social changes so desperately needed. However, without suing cops and governments when dangerous, unethical brutality and abuses occur, police will continue to violate the law unchecked, escalating their unaccountable misconduct and making our communities even less safe.

Two years after the Thurston Hills Black Unity protest, we want to provide our community with an update on SPD and the state of the civil rights lawsuit against Springfield and its cops, Black Unity v. City of Springfield, et. al. You can read the full complaint here.

What Happened?

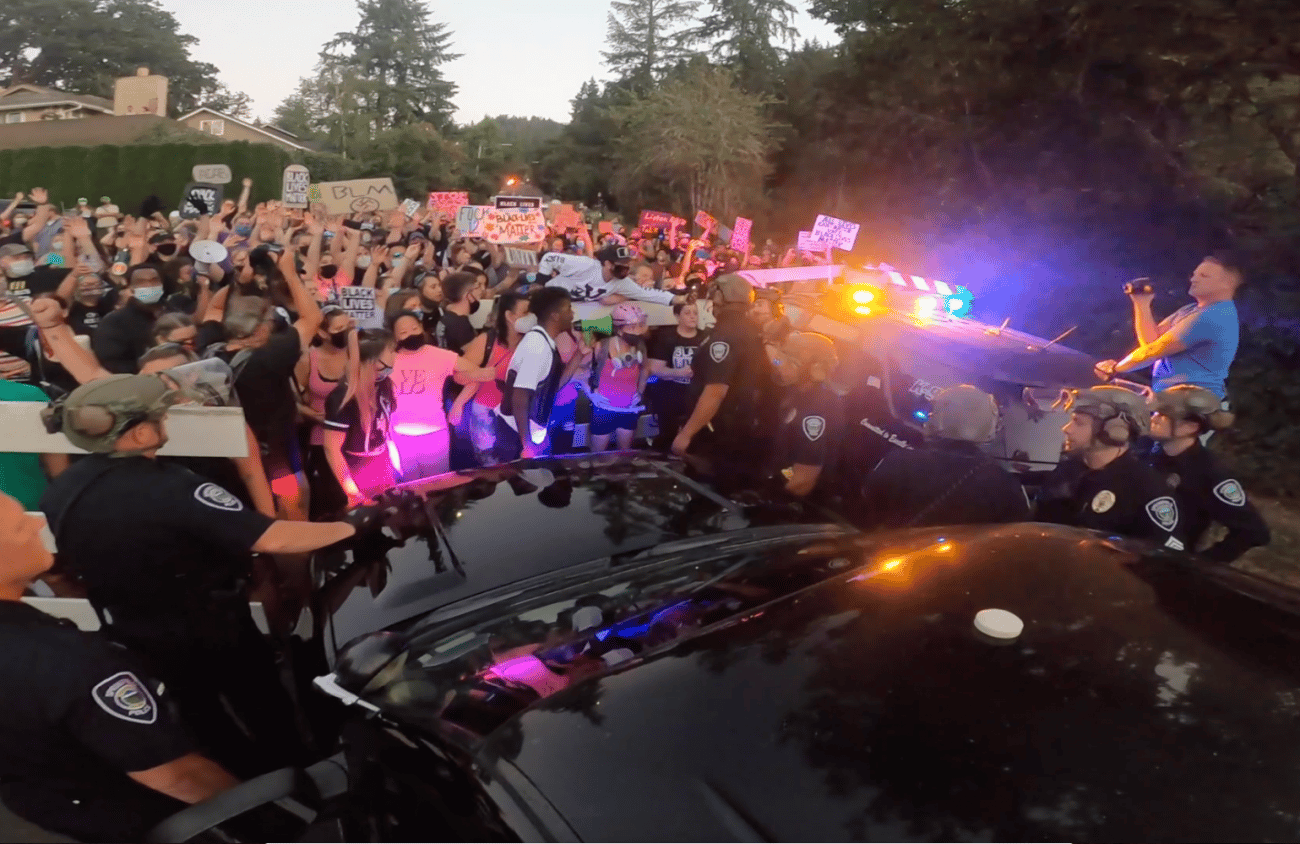

For those who weren’t there, or didn’t hear about the protest, the events are simple enough to explain: Black Unity planned a peaceful march through the Thurston Hills neighborhood after a Black resident reported a skeleton hanging by a noose across from her home. Anti-racist protesters showed up to that neighborhood in solidarity and peacefully marched and chanted, stopping occasionally to give speeches and teach-ins. Some Thurston Hills neighbors joined the protest march, but others appeared to join with counter-protesters who heckled, harassed, and assaulted Black Lives Matter protesters. The march was abruptly halted when SPD erected a line of riot cops behind a flimsy barricade and kettled the marchers. With racist counter-protesters at the rear of the march, and more of them visible behind the barricade with the cops, activists stood at the barricades and chanted, sang, and continued to demonstrate against racism and SPD’s arbitrary restrictions of their right to protest. SPD then rushed the crowd, arresting, jabbing, punching, tasing, and otherwise assaulting protesters. Many people, including CLDC’s plaintiffs, were injured by SPD’s misconduct. Others were also injured when SPD forced the marchers down a gauntlet of armed counter-protesters and then turned a blind eye to the counter-protesters’ assaults on the nonviolent anti-racist protesters. The apparent collusion between SPD and racist counter-protesters was caught on video and further chilled protesters’ First Amendment rights.

Ultimately, ten activists were arrested: nine people were charged with misdemeanors, and one faced felonies. Only one person was ultimately convicted and served jail time—the rest, including the felony charge, had their cases dismissed.

What Are We Pushing For?

CLDC, Black Unity, and several individuals filed impact litigation[1] against the Springfield Police Department, the City of Springfield, and the officers accused of abuse in March 2021. This month, we added new defendants and a new plaintiff, BU leader and activist Jazmine Jourdan. While chanting at the SPD barricade alongside fellow organizer Tyshawn Ford, she was pushed from behind by Defendant Officer Bragg and fell to the ground. Once there, she was brutally beaten in the face and head with closed fist punches by Durrant. At the same time, Durrant lunged and grabbed at Ford, who was also thrown to the ground, repeatedly assaulted, and then dragged behind the police barricade and arrested. In both instances, Durrant used SPD’s controversial “focused blows,” a dangerous street-fight tactic of punching people in the head and/or face with a closed fist. Ms. Jourdan faced trumped-up Circuit court criminal charges, including Assault of an Officer, Interfering with a Police Officer, and Felony Riot. Last month, all of her charges were finally dismissed during trial, and she now joins the other people fighting to try to ensure no one else is subjected to egregious police misconduct in the future.

Even without Covid 19 delays, federal civil rights cases like this can take years to fully investigate and conclude. Litigation is more effective with sustained oversight from the community. Without pressure from the power of the people, SPD and the City may feel less urgency to make necessary changes to the inadequate hiring, training, supervision and disciplinary practices that are clearly lacking in the department. The resignation of the Chief of police will hopefully assist in reforming the racist street-brawler culture that had been permitted and/or encouraged by department leadership, but much more will be necessary to ensure that everyone in Springfield will have their rights respected and will be treated with professionalism and decency.

Currently, the parties to Black Unity v. City of Springfield, et.al are in the discovery phase– exchanging documents and taking depositions to gather evidence for trial. CLDC has obtained hundreds of pages of police reports and hours of body camera footage from the dismissed criminal cases. What we have been able to review so far makes us confident our lawsuit will be successful in holding SPD accountable for violating the constitutional rights of BLM activists.

Most civil rights cases end in a settlement agreement instead of a jury trial. The Black Unity plaintiffs are attempting to reach a resolution that will mandate important structural and policy changes to improve who is hired in the first place, and the culture of training, supervision and discipline within SPD over the long haul. The plaintiffs have provided a list of twelve demands. Briefly summarized, they are:

- Deletion of all records collected or maintained by SPD about lawful political organizing, BU members, and people associated with BU, in accordance with ORS 181A.250, which prohibits cops from spying on activists and political work.

- Written agreement to stop collecting or maintaining information about the political, religious or social views, associations or activities of any individual, group, association, organization, corporation, business or partnership, unless such information relates directly to an investigation of criminal activities, and there are reasonable grounds to suspect the subject of the information is or may be involved in criminal conduct.

- Review and reallocation of at least 20% of current policing budget to CAHOOTS or a similar non-law enforcement program to address the underlying community social inequities. We need more social services, not more armed soldiers jailing people.

- Strengthen internal policies regarding officers’ duty to intervene to stop other officers’ misconduct.

- Appointment of an Independent Monitor to be engaged during any SPD deployment to protests, through the 2024 calendar year.

- Include BIPOC members of the public on police department employee hiring panels and internal affairs investigations.

- Implement a transparent and public citizen complaint system for police accountability, with all complaints against cops publicly available on the internet.[2]

- Prohibit police officers from associating with organizations or people who have a reputation in the community for bigoted and racist ideologies.

- Amend SPD’s Oath of Office to require each officer to disavow racism, bigotry, and hatred based upon suspect classes per Oregon and U.S. constitutional standards, and to promise to actively combat both systemic and internalized racism in their work.

- “Brady Letters[3]” documenting officer misconduct from July 29, 2020, for six of the Defendant officers.

- Improve and implement mandatory, annual anti-racist and bias education, without additional funding, that adheres to best practices.

- Improved Victim Services, to facilitate easier navigation for crime victims, including status of criminal prosecutions.

So far, the Defendants have failed to accept any of these demands or offer any meaningful counter-offers for substantive change. Nevertheless, the Plaintiffs are hopeful for the opportunity to help reform the Department through settlement and expect to go through another round of settlement negotiations this fall.

The Plaintiffs and CLDC recognize that reform is just a band-aid on the inherently racist system of policing. Abolition will not come from police departments agreeing to police themselves. However, we can mitigate the harm people face on a daily basis from what appears to be an outdated, racist, and unprofessional department.

What has changed at SPD since July 29, 2020?

Since July 29, 2020, numerous officers, including the former Chief, Rick Lewis, and former Officer Bronson Durrant, have left the Department. The new Chief, Andrew Shearer, has promised to change the Department’s culture.[4]Numerous other officers were placed on administrative leave and subjected to increased scrutiny because of their misconduct. Because police disciplinary records are kept secret from the public, it is very difficult to know which bad cops were actually held to account for violating their public duties.

Over the last five years, the Springfield Police Department has accounted for over 90% of the millions of dollars paid out by all Lane County policing agencies in litigation settlements. The largest settlement the Department has paid to date, $4.55 million, was to the family of Stacy Kenny, a trans women who was brutally killed by the Department during a traffic stop in March, 2019.[5] As a part of the Kenny settlement, an Independent Critical Incident Review report recommended thirty-three SPD policy changes, including discontinuing the use of “focused blows.”

Similarly, the Department commissioned an Independent Assessment of the July 29, 2020, Thurston incident by a retired police chief, Rick Braziel. The report was generated after the City conducted listening sessions with the community and a selective incomplete review of police records. The Braziel report was released in March 2021 and made thirty-eight recommendations. However, despite the new Chief’s promise to reform the troubled police force, the Department continues to use focused blows, and has failed to adopt any recommendations from the Braziel Report (other than policy changes they were required to make because of State law changes in 2021).[6]

It seems clear that SPD is not interested in becoming a 21st century public safety department even under the new Chief’s leadership. Last month, the Eugene Police Department brought in the SPD riot squad to break up a protest for reproductive justice after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. Once again, people were subjected to excessive force and several were injured by overreactive militarized cops, including SPD Officer Bragg, who was responsible for aggressively shoving Ms. Jourdan with his baton during the Thurston Hills protest.

Endless Pressure, Endlessly Applied

Oregon has a long history of racism, and its tenacity is often seen in small town and rural police departments today. That’s part of why CLDC is so committed to working with Black Unity to ensure that the Black Unity v. Springfield lawsuit brings about real change in a department that has long resisted it.

Many more people were affected and injured on that day than are included our lawsuit. Understandably, not everyone can join such a suit due to the immense pressure it places on their time, their families, and even their mental health, as they are placed under scrutiny in their pursuit of justice. With this litigation, Black Unity and CLDC seek a future Springfield in which all BIPOC can assert their rights without fear of violent repercussions from agents of the State. If you are an affected community member who has ideas of how to reduce harm and racism in the Springfield Police Department for people of color and protesters, please share your thoughts with CLDC. Learn more and get involved at cldc.org.

The Civil Liberties Defense Center is a nonprofit organization of lawyers and movement professionals who seek to dismantle the political and economic structures at the root of social inequality and environmental destruction. We provide litigation, education, legal and strategic resources to strengthen and embolden environmental and social justice movement success.

Citations:

[1] Impact Litigation refers to the strategic process of selecting and pursuing legal actions to achieve far-reaching and lasting effects beyond the particular case.

[2] see https://www.chicagocopa.org/data-cases/case-portal/ and https://invisible.institute/police-data/ for examples.

[3] Prosecutors are required to identify and disclose to the defense police officers whose past conduct might raise questions about their fairness or truthfulness as a witness in a trial.

[4] https://www.kezi.com/news/andrew-shearer-officially-sworn-in-as-springfield-police-chief/article_d617b52a-aefe-11ec-9f9e-7f3c0325bffd.html

[5] https://www.registerguard.com/story/news/2021/03/31/report-springfield-police-failed-to-de-escalate-before-shooting-stacy-kenny/4807251001/

[6] https://www.opb.org/article/2021/04/27/oregon-lawmakers-ok-police-accountability-measures/